Written by David Muise | Photography by Jose Leiva

Imagine for a moment that your job description included running headlong into pitch black and very tight spaces. Or finding minuscule amounts of a substance in cleverly hidden places. You might be expected to enter an unknown area, occupied by a potentially lethal character, and to unnaturally ignore the concept of fear. And for all this, the reward may be a treat or a simple meal. If you’re really lucky, you might even get a toy.

This work is the domain of police dogs, or canines called “K9s.” Together with their handlers, they form highly disciplined and specialized units that do some of the most difficult work in policing. From sniffing out drugs and apprehending dangerous criminals, to peforming search and rescue, these teams are at work in our community, often unnoticed, providing an invaluable and wholly unique public service.

The dogs

If you went by Hollywood standards, you would probably think that the German Shepherd is the only breed suitable to be a police dog, since it is so commonly associated with the work. But according to Christian Stickney, owner and lead trainer of North Edge K9, we may have it wrong.

“Almost any dog can be trained to do at least the scent-based work: hounds, labs, retrievers,” Stickney clarifies.

Stickney would know, having bred and trained hundreds of dogs over his career with North Edge. He has also run the K9 unit at the Gorham Police Department for over 20 years.

He defines the two main types of work most often done by police dogs: scent-based work and patrol work. K9s are referred to as either “single purpose,” deployed for scent-based work only, or “dual purpose,” deployed for both scent-based and patrol work. Each type of work demands certain characteristics from a dog.

“For patrol work, there are certainly some preferred breeds. Yes, the German Shepherd is one of them but, increasingly, the Belgian Malinois is being used, as well.” He adds, “That’s my personal preferred breed for patrol work.”

Both German Shepherds and Belgian Malinois have the right temperment for patrolling. They both learn commands for a variety of tasks quickly and easily, and both exhibit unflinching confidence. Moreover, they are both supremely loyal breeds; it would seem their purpose in life is to be the courageous protector and constant companion of their human partner.

While these breeds may be the most coveted for dual purpose work, there are other breeds that currently serve in the capacity of patrol work, around the world. The most important factors, according to Stickney, are the traits an individual dog displays, as it is being trained.

“Not every dog is cut out for police work,” says Stickney. “Even after training, some dogs just don’t naturally possess the key traits we’re looking for.”

The four traits

Beyond breed, each dog has its own personality. Working with a dog helps to illuminate character and gives trainers a clearer picture of the dog’s suitability for law enforcement work.

“There are four key things I’m looking for in a dog that could potentially be doing police work: sociability, environmental soundness, hunt drive, and interaction,” Stickney enumerates. “It takes some time working with a dog to notice these things.”

Creating a K9 Officer

Stickney offers insight into the reward system most K9 units employ with their dogs. This technique becomes the cornerstone to a K9’s ongoing work and training.

Stickney offers insight into the reward system most K9 units employ with their dogs. This technique becomes the cornerstone to a K9’s ongoing work and training.

“Think of a bottle cap- it doesn’t mean anything to you, right? I mean, it’s just a bottle cap,” posits Stickney. “But what if I told you that I’d give you 10 bucks every time you went over and touched it? You’d be touching it as often as you could. That’s kind of how K9s work.”

K9s learn this reward system during their rigorous training program. Just to become certified as a working police dog in Maine, a dog and his handler will go through about 480 hours of training together, before even taking the state examination test. The comprehensive test includes basic obedience training, off-leash work, tracking over multiple terrains and surfaces for 30-minute periods, and the display of effective dog control. Even after passing, the work continues with just as much vigor, as the certification must be renewed annually and training goals must be met quarterly.

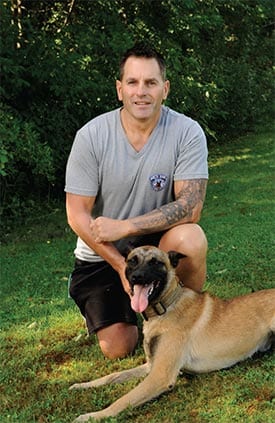

“This is pretty much a 24/7 job,” describes Officer Kevin Gagne from the Lewiston Police Department of the work he and his K9 partner, Scout, perform. “Not only do we train formally for 16 hours a month, but we are training nearly every day. Really, everything is a training opportunity.”

Rewards for K9 work

Professionally trained K9s stay motivated through a system using food, toys and treats. These, along with the desire to please their handler, form the backbone of K9 work.

K9s are first taught to respond to food rewards. Officer Gagne explains that the food reward is different each time Lewiston K9 Scout earns one.

“Sometimes she gets a lot of food, sometimes she gets a little. Occasionally, she even gets a liver treat,” says Gagne. “If I’m working outside the house, then I’ve got food in my pocket for potential reward scenarios. The goal is that she’s always motivated and hoping for the big payout.”

Officer Don Cousins, of the Auburn Police Department, uses the toy reward system with his K9, Rocky.

“Rocky gets a rubber ball to play with, as a reward for doing police work,” says Officer Cousins. “When I first got him, all we did was train like this. It’s ingrained in him- do the work, get the ball.”

Most K9s in Maine live with their owners, usually in a kennel. Home-based training adds to the training capability of the handler, and makes the job a 24/7 endeavor.

“I’d have my daughter go sit in the woods and send Rocky out to find her. Then I’d reward him with his ball,” says Cousins.

The nose

While a human has about six million olfactory receptors in its nose, it is believed that a dog has about 300 million. Further, the part of a dog’s brain devoted to analyzing smells is, proportionately, 40 times greater than in humans.

What are the implications? Officer Gagne explains a dog’s ability to differentiate scents like this:

“Say you walk into a house, in the winter maybe, and you smell the recognizable scent of beef stew. You know it well; it smells familiar. Well, a dog walks into that same room and smells beef, carrots, onions, potatoes, broth- each individual ingredient in the beef stew- uniquely.”

“Say you walk into a house, in the winter maybe, and you smell the recognizable scent of beef stew. You know it well; it smells familiar. Well, a dog walks into that same room and smells beef, carrots, onions, potatoes, broth- each individual ingredient in the beef stew- uniquely.”

Stickney uses another scenario to further explain how incredibly small amounts of residue can leave behind a detectable scent for a K9 to hit upon:

“You walk into a room that smells of popcorn. You know it, even though there is no sign of popcorn. Even trace amounts of narcotics are like that smell of popcorn, to K9s.”

Scientists around the world are learning the mechanics of dogs’ unique abilities in scent detection. For example, dogs have the ability to separate the air they breathe in for respiration purposes and the air that contains smells. A portion of the air breathed in as scent gets trapped in a recess in the nose that is dedicated to olfaction, or scent detection. There, the air gets filtered and olfactory receptors within the tissue “recognize” odor molecules. These receptors send electrical signals to the brain for individual analysis.

This helps explain how K9s, like Officer Gagne’s Scout and

Officer Cousins’s Rocky, can detect trace amounts of narcotics even when these substances are disguised with other smells, and how they can pick up an individual human’s scent for tracking purposes.

Working officers

Every K9 officer has incredible stories to tell about the often dangerous work performed by their canine partners. Stickney pointed us to a Facebook page called “Law Enforcement Dogs of Maine” that, among other things, highlights many of the achievements of law enforcement efforts of K9 units around the state. The page is filled with awe-inspiring stories of K9 unit work that often don’t make it into the headlines. On this page, one can find myriad ways these units are working every day to make our communities safer.

Every K9 officer has incredible stories to tell about the often dangerous work performed by their canine partners. Stickney pointed us to a Facebook page called “Law Enforcement Dogs of Maine” that, among other things, highlights many of the achievements of law enforcement efforts of K9 units around the state. The page is filled with awe-inspiring stories of K9 unit work that often don’t make it into the headlines. On this page, one can find myriad ways these units are working every day to make our communities safer.

Law enforcement dogs are on the job every day all across Maine. They are often the very first to be deployed into highly dangerous environments. Stickney shared a personal story of just such an incident.

“We were called to a break-in in progress. A guy had entered a house and the owners ended up barricaded in on the second floor. After we arrived, the guy emerged threateningly- with a lead pipe, posing a risk to officers’ safety,” he recounts. “I deployed my canine, and the situation was deescalated- to the point where we were able to safely apprehend the suspect without any harm to anyone.”

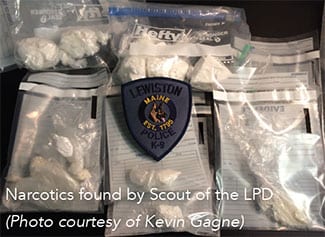

That is just a single story of the bravery and service a patrol dog offers on the job. It’s no different for K9s doing scent-based work. Officer Gagne’s K9, Scout, is just as busy sniffing out and ridding the streets of the many dangerous narcotics that are plaguing our communities. In fact, Scout answered 122 calls for service last year alone.

That is just a single story of the bravery and service a patrol dog offers on the job. It’s no different for K9s doing scent-based work. Officer Gagne’s K9, Scout, is just as busy sniffing out and ridding the streets of the many dangerous narcotics that are plaguing our communities. In fact, Scout answered 122 calls for service last year alone.

One memorable service call for Officer Gagne came when Scout was deployed in a house where a search warrant had been issued. Scout detected two locked safes, one of which was well hidden and the other was in a mattress. She also picked up the smell of narcotics inside a couch. These are especially difficult situations in which to find narcotics, and certainly could have eluded the human officers’ search. All told, Scout helped take hundreds of grams of lethal drugs off the streets.

The proviso

Each officer we spoke to touched on one important fact they want the public to know: K9 dogs are working law enforcement professionals. They are also “tools” used by law enforcement officers; as such, K9s should not be treated as pets.

“In addition to handling our K9s, we carry a gun, Taser, communications equipment. You wouldn’t ask if you could touch any of those tools, right?” reasons Stickney. “It’s the same with the K9s. They are also tools we use to complete our police work.”

Their handlers want you to know that you need to respect these animals. You can do that by asking permission to touch or pet the dog, and understanding that it’s often not appropriate to do so.

Finally, you should know that these animals and their handlers are out protecting our community on a daily basis. Their work may not always be in the public eye, but they grind away every day and do the hard work that safety demands.

“It is very gratifying work,” says Officer Cousins. “Every time

the training comes together, any time you see the hard work pay off, it makes it all worthwhile. Especially, if you love dogs.”

North Edge K9

50 Dunton Lane, Gorham • www.northedgek9.com