Written by Kiernan Majerus-Collins | Photography by Mykùl Rojas

When Sabrina York walked into The Store Next Door at Lewiston High School, she didn’t realize her story was anything unusual.

When Sabrina York walked into The Store Next Door at Lewiston High School, she didn’t realize her story was anything unusual.

“When you live it for so long, it’s just life,” York relates. “It doesn’t feel that different or weird, or like it’s not supposed to be like that.”

But York’s situation was different. She was homeless, as a high school freshman.

With her mother battling inner demons while living in an apartment without electricity or much food, York had to stay elsewhere in order to have a safe place to sleep at night. She recalls she would crash with friends, grateful to have a couch.

“If you’re ‘couch surfing,’ which was pretty much what I was doing at the time,” York says, “you’re considered homeless.”

Her unstable home life made school difficult. She said she couldn’t attend summer school because she didn’t have an alarm to help her get to school on time.

Things began to get better, however, when she connected with Mary Seaman, the homeless liaison at Lewiston High School (LHS) and founder of The Store Next Door (SND).

Seaman provided immediate help—York got food, a winter coat, and other essentials, but Seaman also helped York get her own efficiency apartment during her junior year of high school.

Anything a student needs

Jamie Caouette, who currently runs The Store Next Door, said that’s exactly what the nonprofit is designed to do.

“We try to provide anything a student needs to get through the school year. When school starts, students can come down and get any school supplies they need,” Caouette says.

She also stocks underwear, socks, deodorant, and shampoo, and runs a small food pantry. Caouette says these are the kind of items needed by the nearly 300 homeless youth annually who receive aid and support from SND.

For over two decades, this nonprofit resource has been tucked into a couple of rooms in the basement of Lewiston High School.

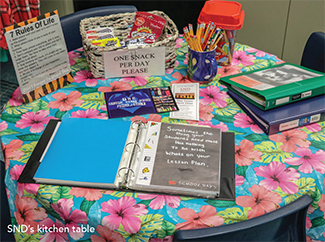

Caouette makes the most of the space, packing in clothes racks, shelves of toiletries and food, a refrigerator full of water and snacks, and a homey kitchen table covered with a brightly colored tablecloth.

“A lot of kids come down in the morning and they have breakfast at the table, like you would at home,” Caouette reports. “The kitchen table means a lot to the kids, because they’ve never had that before.”

Students stop by throughout the day as well, to grab a snack or just take a quick break from the stressful environment that is high school. This cozy and welcoming room gets “very crowded” with all the kids who need help, Caouette says.

Homeless youth get more from the SND than just essential items. Caouette knows that many have had little parental support, and she tries to fill the void as best she can.

Homeless youth

Caouette feels the public has a false image of homelessness. “When you see the man on the corner asking for money, or you see them pushing the grocery cart, that’s your image of homelessness,” she says. “You don’t want to think that there’s homeless youth, but there are so many.”

York’s situation was far from the worst the SND has seen. While most of these teens are “couch surfing” at friends’ homes, York says, some are sleeping outdoors.

Caouette reports some of her homeless students sleep in tents by the Androscoggin River during the summer months. She says she worries about them, especially in the winter when temperatures plunge. Caouette often gathers up bags of food and clothing and roams these areas, just to deliver extra help to these students when they’re not in school.

York and Caouette agree that 90 to 95 percent of the youth served by the SND are dealing with parents who struggle with alcohol or drug addiction. York finds that too many of the students, especially those who don’t get help quickly, head down the same path.

Caouette says the problem is “parents not being parents.”

“Just a couple of years ago I had one student. He went home from school and his neighbor told him that his mom and his younger brother had moved to Alabama while he was at school, and just left him here,” Caouette says. “He was just 15 years old.”

Some students are dealing with even more horrific situations. But with help from SND, they manage to graduate and find their way at a community college.

I can’t see it fall

The 2018-2019 school year was the first since program founder Mary Seaman retired, and Caouette admits it was a struggle. “My role is not really to run The SND, but the need is there” she says.

Caouette actually works for Health Affiliates Maine, as a case manager embedded at Lewiston High School. Her work with homeless and pregnant teens there is funded by MaineCare.

Caouette actually works for Health Affiliates Maine, as a case manager embedded at Lewiston High School. Her work with homeless and pregnant teens there is funded by MaineCare.

Up until this most recent school year, Caouette helped Seaman run The SND, but now Caouette runs the nonprofit with help from an educational technician.

For now, the school system funds the ed tech position. But Caouette knows the threat of budget cuts is real, and would be devastating to the SND.

“This isn’t just a job, for me,” Caouette says. “I know that the SND is so badly needed that I can’t see it fall.”

Caouette remains optimistic, however—she knows that the SND exists because of the generosity of countless members of the Lewiston Auburn community, over the past two decades.

“Everything comes to us from the community,” says Caouette. “I wouldn’t be able to do it without them.

Jamie Caouette and her students would greatly appreciate any donations of money, clothing, food, school supplies, toiletries, or other items.

Reach out to Caouette at

jcaouette@lewistonpublicschools.org

or drop off donations at the Lewiston High School front office.

Kiernan is a writer, activist, and Bates College graduate who lives and works in Lewiston. He serves on the Androscoggin County Budget Committee and as chair of the Lewiston Democratic Party. Kiernan is a member of the First Universalist Church in Auburn, where he sings in the choir and directs the children’s choir. In his free time, Kiernan enjoys reading American history and watching the Boston Red Sox.