Written by Toby Haber-Giasson

“Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain”

– from “The Deserted Village” by Oliver Goldsmith

Local legend credits Mrs. James Goff, wife of a wealthy local merchant, with selecting Auburn’s name from the opening line of an 18th century poem. In it, the writer laments a beautiful pasture squandered for a wealthy man’s residence.

What’s in a name?

The poetic reference behind Auburn’s name would suggest that its land was a precious commodity. Yet, it was Lewiston land that lured English settlers north to Maine.

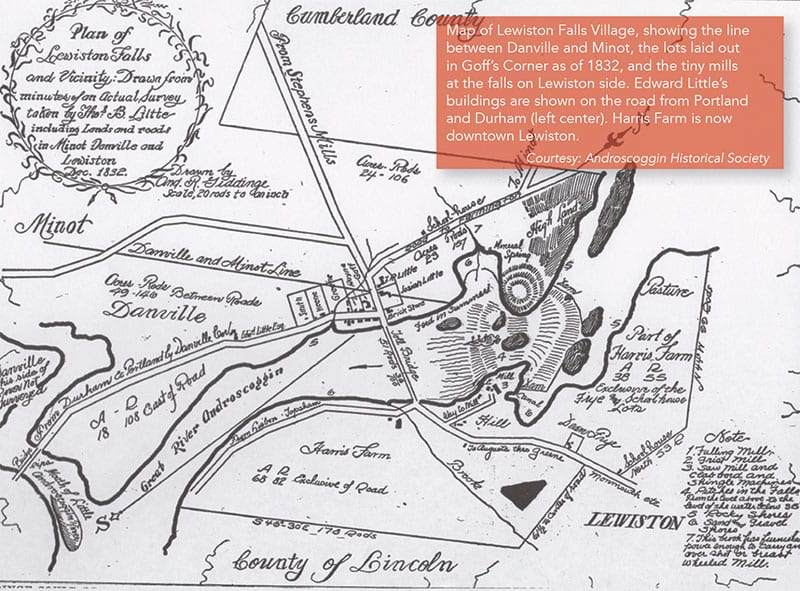

Massachusetts, like England, was getting crowded; dividing up land to succeeding generations was leaving farmers’ sons desperate. In the 1700s, former Revolutionary War Colonel Moses Little, Lewiston’s first realtor, sold such men 100-acre farm parcels to build their dreams on. Little’s son Josiah also spent his life developing Lewiston. In fact, when the colonel’s grandson Edward proposed to build a new home across the Androscoggin River- on the Auburn side- Josiah thought him mad.

Go with the flow

Was Auburn’s water sweeter than its land? Of Auburn’s 50 square miles, 15 percent is water; Lake Auburn alone comprises eight square miles. And that’s not counting the mighty Androscoggin and its other rivers, ponds, and streams.

Alas, Auburn could not transcend its own geography. The Great Falls made for a pretty view, but could only be dammed from the Lewiston side, to the east; Auburn’s dramatic “west pitch” proved too steep to accommodate a water wheel. Instead, early manufacturers utilized Auburn’s abundant lakes and streams for water power. This gave rise to early Auburn shoe and textile shops, as well as grist, saw, and wool-fulling mills.

Alas, Auburn could not transcend its own geography. The Great Falls made for a pretty view, but could only be dammed from the Lewiston side, to the east; Auburn’s dramatic “west pitch” proved too steep to accommodate a water wheel. Instead, early manufacturers utilized Auburn’s abundant lakes and streams for water power. This gave rise to early Auburn shoe and textile shops, as well as grist, saw, and wool-fulling mills.

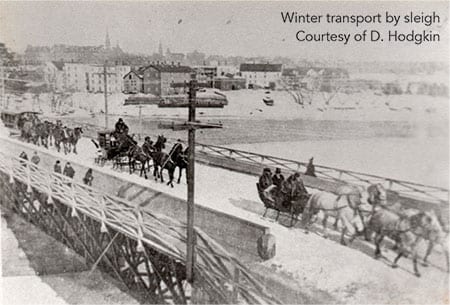

Waterways provided transportation as well. Early ferries took settlers across the Androscoggin River. When rivers froze in winter, they turned into highways for sleighs. Indeed, too much water- during the floods of 1896 and 1936- has profoundly shaped the city, for better or worse.

The forest for the trees

Both land and water were naturally limited resources. With Maine’s cold winters, farming was strictly a subsistence venture, and only the rich elite controlled the waterpower. In reality, Auburn’s economy was founded on neither land nor water: logging was king.

Col. Moses Little himself got his start in the region by harvesting sturdy Maine trees for ship masts. The forest economy offered many job opportunities in cutting, processing, and transporting wood. Hardy men labored long, lashing logs together into rafts, sending them downriver to the sawmills, to become lumber or shingles. But of course, these men wanted to reside near their jobs, in Lewiston.

Early settlement

In colonial times, land grants were given to moneyed nobles and entrepreneurs to promote settlement. Agents could keep choice property for themselves, on the condition of settling a minimum number of persons in a set time period.

The Pejepscot Proprietors obtained such a royal grant in 1768. Col. Little and his partners had the task of luring 50 families to settle in Lewiston by 1774. Local historian Douglas Hodgkin dubbed them “land barons of the Androscoggin River Valley.” Hodgkin, professor emeritus of political science at Bates College, is also curator of the Androscoggin Historical Society and the author of several fascinating books about LA history.

In his definitive work, Auburn 1869–1969: 100 Years a City, written for the city’s centennial, Ralph B. Skinner demystified the origins of Maine’s early white settlers. And who were they? Veterans of the Revolutionary War, given land grants as payment for military service. Sailors who slipped off British ships, seeking a new life. Young men from both England and New England, bucking inheritance customs, whereby sons split their fathers’ acreage.

The pace of early change was glacial. Ferries operated from the Lewiston side as early as 1771, but not until 1797 was there even one permanent structure on the west side of the Androscoggin: a lone log cabin used seasonally by a logging boss named Joseph Welch. Only Turner resident Jeremiah Dillingham followed, building a gristmill at the foot of the falls. Onlookers called the isolated area “Pekin.”

A bridge, built in 1823, bankrolled by Josiah Little, proved the catalyst. Seeing an opportunity, enterprising Jacob Reed hauled a building across the frozen river ice to Pekin. On Welch’s cabin site, Reed opened a general store with a partner, one James Goff, Jr. The popular store became the village center and later would become Goff Block. As Goff became a principal landowner and opinion-leader in town, Pekin became known as Goff’s Corner for a time.

In time, Reed sold his share and opened a tavern down the road. Other shops in the village included a tavern, a millinery (a shop for fancy ladies’ hats), a blacksmith, and the law office of Squire Edward Little.

Little: big man

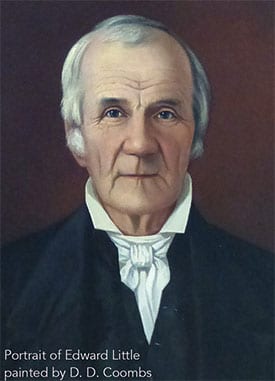

Hodgkin’s fascinating biography, Dear Parent, reveals the quintessential Edward Little through his letters. The success story of the “father of Auburn” is a strange twist on the familiar Horatio Alger trope: a tale of riches to rags…to riches.

Educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Dartmouth College, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa, Edward Little carved out a niche practicing law in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Like many wealthy gentlemen, he engaged in politics, business, and land speculation, until fire and economic downturns wiped out his finances. He relied on his father Josiah’s deep pockets to bail him out.

Deep in debt, he moved to Portland, in what was then the District of Maine, to work for the family business, Pejepscot Proprietors, helping his brother oversee his father’s farms, mills, and logging interests. This payback for his father’s support essentially meant working gratis, so Little generated a modest income by running a bookstore and lending library. Another fire in 1817 left him so indebted that he was arrested and put in debtors’ prison. Would our founder’s fortunes never turn?

At last, destiny called. When poor health befell both his father and brother in 1826, Little took charge of Pejepscot Proprietor’s LA office. And destitute though he still was, the gentleman lawyer was appointed justice of the county court by the governor. The catch: he had to reside in Cumberland County, on the eastern side of the Androscoggin River.

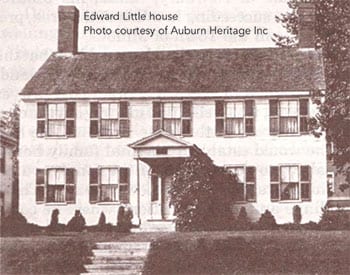

And so, although his family had devoted a century to the town of Lewiston, Little constructed a grand family homestead on the wrong side of the river, in an area formerly part of Danville. The Edward Little House, completed in 1827, still stands at Main Street and Vine in Auburn.

And so, although his family had devoted a century to the town of Lewiston, Little constructed a grand family homestead on the wrong side of the river, in an area formerly part of Danville. The Edward Little House, completed in 1827, still stands at Main Street and Vine in Auburn.

With the inheritance he received upon his father’s death, Little stabilized his finances and looked outward. He strategically developed Danville, still a rustic wilderness, into what we now know as Auburn’s downtown. Little created a village center complete with civic amenities: streets, post office, and a cemetery. He helped build a Congregational church at Main and Drummond Streets, which later established its home on High Street. He founded a school of great repute, the Lewiston Falls Academy, on his rye field. This became the original Edward Little High School, then Central and Great Falls Schools, and the current home of Community Little Theater.

Annexation showdown

Yes, dear reader, you may note the irony that Little’s civic accomplishments were actually made in Danville. Auburn was actually created from fragments of two neighboring towns, Minot and Danville.

“In fact, there were more houses and shops than on the Lewiston side,” Hodgkin relates. “What it lacked was an independent existence.”

Auburn did not even exist as a proper entity until 1842, well after European settlers ventured there.

At the proposal of our friend James Goff, Jr., and against the will of a majority of voters in Minot, the state Legislature ceded a section of Minot, along the so-called “curve line,” to create Auburn township in 1842. This “curve line” is still the western boundary of the city.

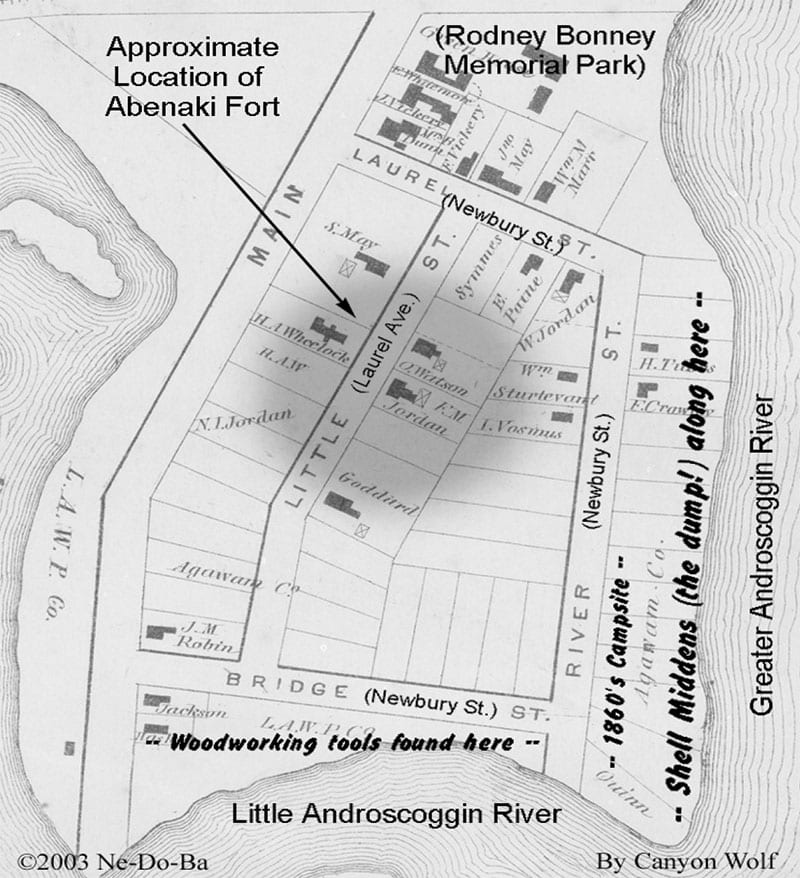

At that time, the town of Danville included the land north of the Little Androscoggin River. This area, the original site of the Abenaki village of Amitgonpontook, spans from the falls down Main Street to Laurel Hill. So how did it become Auburn as we know it?

“Wonderful story!” exclaims Professor Hodgkin.

By 1859, many in Auburn felt the divided villages should be unified into one. Others felt Auburn should annex part of Danville. Not surprisingly, neither scheme appealed to residents of Danville.

The state Legislature held a hearing where multiple arguments were presented in favor of union. Residents of the parcel in dispute had to travel five miles just to get their mail at the Danville post office, let alone vote in Danville town meetings. Some landowners were paying taxes to both towns, because their homes straddled the town line. Union prevailed; Auburn got its little piece, and the town of Danville was diminished but survived; its voters opposed union by 2:1.

Whither Danville?

So why is Danville (née Pejepscot) no longer a sovereign town? In 1867, the rest of Danville was annexed to Auburn- against their will- in an even more contentious showdown.

So why is Danville (née Pejepscot) no longer a sovereign town? In 1867, the rest of Danville was annexed to Auburn- against their will- in an even more contentious showdown.

A proposal was brought forward to annex the town. The Legislature was inclined to allow it. It was customary to let town residents vote on such matters, as a courtesy. However, many wanted to dispense with this practice on two

grounds. One reason was the fact that a majority of Danville residents was opposed to the merger, which would kill the measure. The other, the voters of Danville were predominantly Democrats; in fact, Danville was the only Democratic town in the county. Therefore, a merger would erase not only the town, but would drown this Democratic Party stronghold out of existence.

The Legislature passed the bill, contingent on approval by a majority of combined voters in the two towns. The selectmen of Danville defiantly refused to hold a town meeting to vote on annexation. But the state Legislature held that, if Danville would not vote, it would still pass the merger, like it or not. Auburn officially became a city in 1869.

“They are still mad, to this day,” notes Hodgkin of Danvillers. And it’s no wonder; Danville’s antics had backfired, and they were gone.

People of the Dawn

Far beyond the relatively brief scope of Auburn’s 150-year history, a native civilization existed here, for some 12,000 years. Abenaki (also called Wabanaki) people inhabited a wild paradise between the Great Falls and the Little Androscoggin River.

They called it Amitgonpontook. Though translations have been attempted, according to Nancy Lecompte, research director of Ne-Do-Ba, “The name’s meaning has been lost to time.”

The Abenaki villagers existed in harmony with nature, cultivating corn and enjoying bountiful fish and game. A stockade, built on the high ground of Laurel Hill, protected women and children while the men went hunting.

The very presence of Europeans in Maine wrought terrible consequences for the native people. Strange new diseases, for which Abenakis lacked immunity, wiped out 75 percent of native peoples in the 1600s. One estimate, cited in Lecompte’s book, Alnobak, shows their population plummeted from 20,000 to about 5,500.

The environment suffered, as well, from the Europeans’ ways. Aggressive logging practices decimated the old forests; without the moderating effects of trees, soil eroded. Wasteful farming practices despoiled animal habitats for game. Dams made it impossible for migratory fish to spawn, as they had for centuries. Growing amounts of domestic livestock required more and more land to be cleared.

In order to survive, Abenakis’ livelihood shifted to trade with the French. Many natives allied with the French against the English in their century of wars. Captured prisoners were often kept here, at Amitgonpontook.

Then, one September day in 1690, a British reconnaissance party rescued several white captives being held in the stockade. As an act of vengeance, General Benjamin Church destroyed the entire settlement. Food stores and dwellings were burned, and unknown numbers of Abenakis were killed.

Celebrate Abenaki history and culture:

- www.nedoba.org – a 501(c)(3) Maine Nonprofit Corp.

- Abenaki artifact collection at the Androscoggin Historical Society

- “12,000 Years in Maine” at the Maine State Museum

- “Holding Up the Sky” at the Maine Historical Society

Toby hails from the bustling New York City world of P.R., promoting live events like pay-per-view boxing, and publishing album reviews in Creem and Audio magazines. ---

In LA, she coordinates events for First Universalist Church of Auburn, hosting the monthly Pleasant Note Open Mic, and staging their annual “Vagina Monologues” benefit against domestic violence.