Written by Toby Haber-Giasson

Taking a toll

In the beginning, native Abenakis plied the Androscoggin River by canoe. Early European settlers to the Androscoggin Valley rode to Lewiston on horse and wagon. Although ferries did cross the river, there was meager interest in Auburn as a destination.

Yet a group of private investors, headed by city patron Edward Little, built a toll bridge across the river’s expanse. The site was just upriver from the current Longley Bridge.

Yet a group of private investors, headed by city patron Edward Little, built a toll bridge across the river’s expanse. The site was just upriver from the current Longley Bridge.

The process of building this structure, for the monocle-popping sum of $3,000, was fraught by power plays, cost increases, and delays. But this bold gambit, completed in 1823, rang true to the adage If you build it, they will come. Traffic increased steadily to and from what is now downtown Auburn, along with growth in commerce and population.

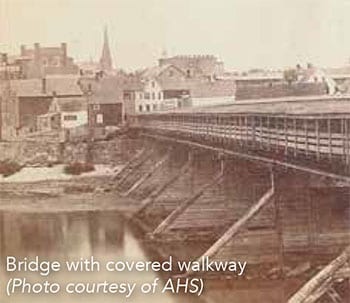

Over time, the primitive wooden bridge deteriorated to the point that four cows fell through the boards into the river. The structure was renovated in 1837 as a covered bridge with a walking lane.

“People hated the covering,” says Douglas Hodgkin of the Androscoggin Historical Society (AHS). “The pedestrian sidewalk was dark, and both ladies and men didn’t like it- who knows who was lurking in the shadows!” In 1849, a wider open bridge was developed, with covered sidewalks.

Tolls gradually rose, as prices do. Patrons who grew tired of paying to cross back and forth each day petitioned the county in 1863 to build a competing free bridge. One afternoon, when anger reached a fevered pitch, wagon drivers staged a blockade to protest the tolls. Soon after, the owners sold the bridge to the county for $7,500. The people had spoken!

Railroaded

Inland from the Androscoggin River, several small villages had arisen, due to two factors: water and transportation. A stream that flowed into Big Wilson Pond (now known as Lake Auburn) powered several small shoemaking shops. These “manufactories” made use of the stagecoach run, which passed through these areas, to deliver shoes between Portland and Farmington.

All that changed in 1848. Railroad tracks were laid right through Goff’s Corner. The original station was near Minot Avenue; later a new one was built on Railroad Street. The Androscoggin & Kennebec Railroad steamed through Lewiston on its way south from Waterville, connecting with Portland at Danville Junction.

This new infrastructure spurred a gradual migration of shoe shops to Auburn’s downtown. They wanted access to a broader range of shipping destinations via rail.

Littlefield’s bold vision

Auburn’s first elected mayor was Thomas Littlefield in 1869. Over his seven terms, he led major infrastructure projects creating sewers, sidewalks, granite crosswalks and cobblestone paving, and neighborhood schools.

Tony Beaulieu, Auburn’s city engineer, says those features have long since been replaced. “Auburn spends two to three million dollars annually on maintenance of roads and sidewalks. We use plastic pipe for new sewer and storm drains, water and natural gas.”

Another Littlefield accomplishment: a complete rebuild of the bridge in 1871. Through cooperation with Lewiston, both cities issued bonds for the project totaling a whopping $40,000. Unfortunately, they rejected a design with iron piers for $50,000; a sturdier structure would have saved the cost of subsequent rebuilds, when floods repeatedly washed out the bridge. For some perspective on the expenditure, the Maine Department of Transportation ballparks the cost of building a modern bridge today at $30 million.

The original South Bridge, later renamed the Bernard Lown Peace Bridge, cost $43,000 to construct in 1874, an expense shared by the cities and the waterpower company.

Beating a monopoly

Meanwhile, steam rail operator Maine Central had taken over Androscoggin & Kennebec Railroad (A&K) and other local lines. Without competition, they did what a monopoly does: raise rates ever higher. Chafing under high shipping prices, local manufacturers sought instead to take their business to The Grand Trunk Railroad Company (GTRC), which linked Montreal to Portland via Danville Junction. But the GTRC didn’t want to provide the connector.

Mayor Littlefield presided over a controversial plan for the cities to build a branch line together. Lewiston put up $224,000 for its share; Auburn shelled out $74,000, even as the plan changed to build Lewiston Junction on Lincoln Street. Shrewd Littlefield leased the rail line to the Grand Trunk for $18,000 per year, so the capital investment paid for itself.

The five mile branch supported 30 freight runs and 12 passenger trains daily. In its first year (1874), 35,000 passengers, many of them French-Canadian immigrants from Quebec Province, arrived at the Grand Trunk Depot (recently operated as Rails restaurant). The line still operates today, providing freight service to the industrial park. Think of all that history when you’re downtown at a railroad crossing, waiting for the last freight car to pass.

Horsing around

Before the 1900s, livery transportation was the only way to get around town. If you didn’t own your own “gig” (one-horse buggy), you could rent a “hack” (hackney carriage) to get home from the train station. Or you might ride an “omnibus” (covered wagon), for five cents.

Starting in 1881, you could ride the Lewiston and Auburn Horse Railroad. These horse-drawn trolleys ran on metal rails. Rail tracks reduced friction on the wheels, allowing for a smoother ride than the road offered.

Many horsecar routes connected LA: Lisbon Street, Main Street to the old fairgrounds, to Pine Street, to Perryville (Turner, Summer, and Center Streets) and Lake Auburn. By 1890, other routes included: New Auburn, College Street and Dennison Street. Stables for horses, the “engines” of this system, were located at Chapel Street in Lewiston and Lake Auburn Avenue in Auburn. The horse railroad grew to 14 miles of track.

Trolley time

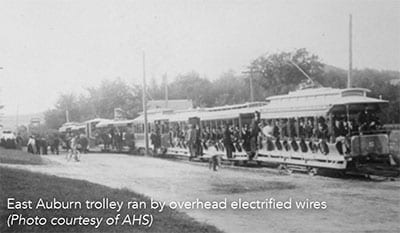

By the end of the 19th century, the advent of electric power brought the gradual replacement of the horse railroad by electric streetcars. Power for these trolleys was supplied by overhead wires, with the type of technology that today runs amusement park bumper cars. By 1894, the Lewiston and Auburn Electric Street Railway debuted on former horse routes.

By the end of the 19th century, the advent of electric power brought the gradual replacement of the horse railroad by electric streetcars. Power for these trolleys was supplied by overhead wires, with the type of technology that today runs amusement park bumper cars. By 1894, the Lewiston and Auburn Electric Street Railway debuted on former horse routes.

LA’s systems merged with others to form the Lewiston, Brunswick & Bath Electric Railroad (LB&B), which had several loops in downtown Auburn, East Auburn, Auburn Heights, and the “Belt Line,” which ran through New Auburn. Over time, service was extended to Sabattus, Augusta, Hallowell, and Gardiner. After 1906, new owners added Mechanic Falls, rebuilt tracks in LA and added the Prospect Hill line in New Auburn. In 1910, a line from East Auburn to Turner was added.

Lake Grove resort

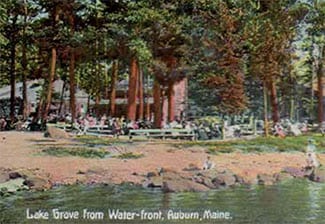

Many electric railways boosted their business by developing tourist destinations. The same people who rode the trolley to work eagerly spent another nickel during their leisure time for some relaxation. As such, Lake Grove resort was created along Lake Auburn in 1883 for LA’s burgeoning middle class.

Lake Grove’s station welcomed visitors in special eight-wheel open cars. Impressive stone pillars marked the entrance. Patrons could enjoy picnics, concerts, fishing, and cycling, dancing, and roller skating. They could visit the pavilion, the outdoor theater, or the zoo, ride the merry-go-round, rent a canoe, or board the steamer Lewiston for a romantic one-hour ride on the lake.

Lake Grove remained a regional draw for decades until 1928, when the rise of the automobile hastened its demise.

Interurban revolution

LA commuters were looking for an alternative to slow steam railroad service to Portland. In 1912, after the LB&B bought the Portland and Brunswick Street Railway, a Portland power company took over the whole enterprise. A network of interurbans in New England connected multiple city transit systems, making long-distance travel possible for common folk.

Industrialist W.S. Libbey bought the Lewiston-Auburn Electric Light Company, in order to modernize his mill and use the surplus energy to power a the line. It took seven years for the route to be completed; sadly, Libbey didn’t live to see it open. From 1914-1933, the electrified Portland-Lewiston Interurban Railroad offered a faster method of making the 42-mile trip.

Service grew in size and popularity to 171 miles of track in the New England region, the biggest in the country, until the rising popularity of cars and trucks cut into the business.

LA by bus and air

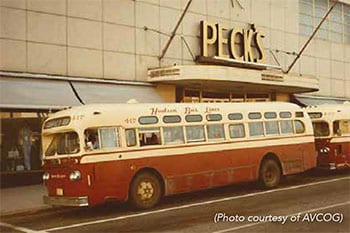

The Lewiston-Auburn Transit Company took over the failing A&K in 1941, converting LA’s electric trolleys to bus service. In 1959, Hudson Bus Lines operated the public transit system, The Bus. According to Marsha Bennett of the Androscoggin Valley Council of Governments (AVCOG), passenger fare revenue was no longer paying for the cost of operation. So in 1976, the cities formed the Lewiston-Auburn Transit Committee, which secured federal funding for public transit. In 1996, Western Maine Transportation Services, Inc. began operating the service for LATC.

The Lewiston-Auburn Transit Company took over the failing A&K in 1941, converting LA’s electric trolleys to bus service. In 1959, Hudson Bus Lines operated the public transit system, The Bus. According to Marsha Bennett of the Androscoggin Valley Council of Governments (AVCOG), passenger fare revenue was no longer paying for the cost of operation. So in 1976, the cities formed the Lewiston-Auburn Transit Committee, which secured federal funding for public transit. In 1996, Western Maine Transportation Services, Inc. began operating the service for LATC.

The city bus system didn’t serve outlying neighborhoods. Residents of Danville, and West and North Auburn, needed a way to get to work at the shoe shops of downtown Auburn. In 1948, Cleba Spofford started the White Line Bus Company with 4 buses. White Line served these outer areas for several years, until a fire destroyed its garage.

Auburn-Lewiston Airport, opened in 1935, is co-owned by the Twin Cities, supporting corporate, charter, cargo, and recreational aviation activities.

Lessons from the past

Who doesn’t love old postcards depicting electric trams? In our search for green alternatives for transit, could trolleys make a comeback?

“It would be a challenge,” says City Engineer Beaulieu. In pursuit of beautification, Auburn has been burying utility lines underground; so much for rehanging wires to electrify a tram.

One notable takeaway is the longstanding cooperation between the Twin Cities on infrastructure, which enabled travel by horse, train, and air. According to Beaulieu, the cities still team up for shared goals like pollution control and water treatment as well.

Salient lesson: transportation drove social change. Maine Memory Network credits transportation with making “new opportunities, both social and economic.” Ordinary people could live even on the outskirts of town and commute to jobs paying a decent wage. Workers could travel cheaper and faster, allowing for more leisure time, and giving rise to the middle class.

As goes Auburn, so goes America!