LA’s most mild-mannered radical activist wields the power of information

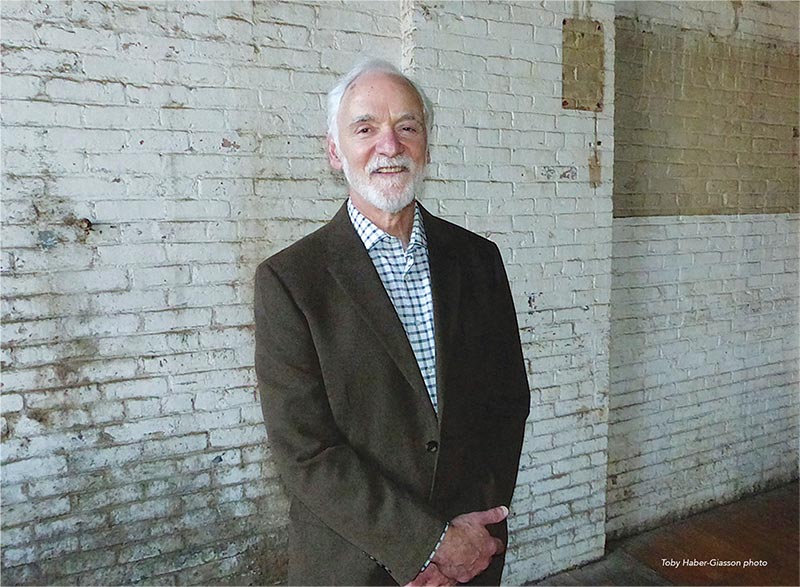

By Toby Haber-Giasson

When Rick Speer sits behind his desk in his top-floor office at the Lewiston Public Library (LPL), he looks upon a series of photos of Mount Katahdin and its rare yet native plants. These vistas have served as a sweet diversion during the busy days that have comprised Rick’s 33 years as LPL’s Director. As Speer unravels himself from his layered civic involvement in the city’s very fabric, he sets his sights on Maine’s natural landscape, which drew him here many years ago.

Ringing tributes

Upon the occasion of his retirement after 33 years as the library’s beloved director, colleagues both within and beyond the library offered heartfelt tributes.

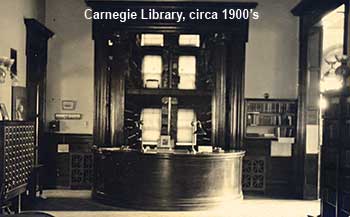

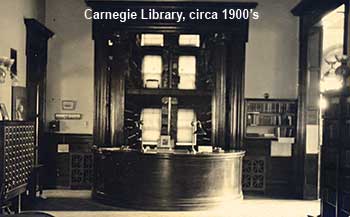

Anne Kemper, a Library Board Trustee, credits Speer’s leadership with transforming the 1903 Carnegie library into “an amazing 21st century learning space” equipped for the needs of the future. Indeed, Speer was instrumental in developing its reach with relevant programming, technical infrastructure and specialized personnel. Kemper extols the library’s extraordinary staff, which exemplifies Speer’s ability to create a “culture of civility and forward thinking.”

Working with Speer over the years inspired Jan Philips, former Chair of the library’s Trustees, to liken him to the Sun. In her astronomical analogy, Speer is LPL’s source of energy and light around which the staff and the board have orbited. An endowment created in his honor had already garnered more than $6,000.

Lewiston’s City Administrator, Ed Barrett, another longtime colleague, recognized Speer’s ability to adapt to change in an age when libraries, as a social institution, have had to evolve. He pronounced Speer’s long-term legacy to be the partnerships he formed with the school committee, other institutions of higher education, and local arts and cultural institutions. Speer’s influence, he said, is now “in the DNA” of the library’s culture.

Somehow, this self-described introvert has achieved this rockstar luminary status with a light touch. Sue Charron will miss weekly administrative meetings with Speer, a fellow department head. As Lewiston’s Director of Social Services, she has seen Rick achieve his goals by plying his wry sense of humor. “He’s a great asset to the city,” she notes.

How does such a humble visionary emerge?

Beginnings

Indeed, how does a man who grew up in a blue-collar town outside Pittsburgh- one that prizes sports and steel- become a librarian? A radical activist librarian, who champions the disenfranchised?

Speer is reluctant to reveal himself- fully. Perhaps Rick’s high school yearbook might tell us he was a track star; we might find a photo of this quarterback of the football team. Or it might tell us what few in LA know: Speer attended West Point. That’s the U.S. Military Academy, at West Point.

And then, as Speer’s daughter Kate put it, “It took books to change that path, in particular, Jerry Rubin’s classic revolutionary book (DO IT!: Scenarios of the Revolution), which questioned the Vietnam war, and had my dad questioning what he was doing at a military school.“ Another influential book for Speer was The Trumpet of Conscience, a collection of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s influential lectures on equality and war.

“I walked in thinking we needed to stop Communism, and walked out questioning what we were doing in Vietnam.” The printed word has spoken to something inside of him. “I couldn’t do it; I had to resign.”

A new path

Speer reinvented himself as a mathematics major at Millersville University of Pennsylvania, but somehow Calculus didn’t look as interesting as his roommate’s library science program. And then, inspiration.

“I took one course and ran into a mentor who changed my life,” Speer recalls of Joe Blake, a professor in Educational Media. “He loved people and culture; he believed in power of information and what it could do for people.” Speer changed course and never looked back.

At college, Speer met another mentor: Jeanne Feight. This progressive librarian hailed from San Francisco, home of the Bay Area Social Responsibilities Roundtable, which promoted the power of libraries for empowering grass roots organizations.

“She inspired me to see that libraries should be both a center and a tool for the community. We should reach out to partners – not just those with power, but to those who lack power, and provide them with the resources to allow them to achieve their goals,” says Speer. “I‘m always attuned to opportunities to empower people; information is power.”

Coming to Maine

Rick Speer met his future wife at a professional conference in 1981. Judith Frost was a member of the Art Library Society of North America, working as a librarian at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Because her family lived in Gardiner, Maine, Speer visited the state. As he fell for Judy’s beauty, he fell in love with Maine’s natural beauty.

The transition was not seamless. Speer is careful to acknowledge Judy’s professional sacrifice for his success; she faced difficulty finding a local position comparable to her role in Cleveland. She struggled for several years before landing her current position as Director of Library Services at Central Maine Community College in 1999.

Collaborating for empowerment

Creating empowerment opportunities at LPL has been Speer’s personal mission: to connect the community by providing the facility and information resources.

Right from the start, Speer noticed LA’s high level of social capital in its social agencies and many talented individuals. “I discovered an amazing amount of collaboration and cross-communication.”

Keen to provide opportunities, Speer capitalized upon these assets by partnering for civic benefit. “I would see ways the library could support organizations.” Here’s just one recent example. “When St. Mary’s Nutrition Center studied food insecurity issues (in 2013), we hosted their gatherings. We worked as part of the Downtown Education Collaborative, driven by Lewiston Auburn College service learning and Bates College’s Harward Center for Community Partnerships.”

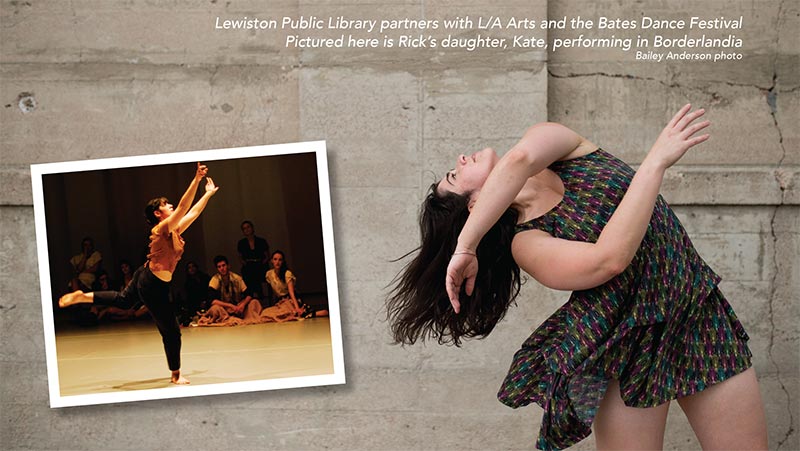

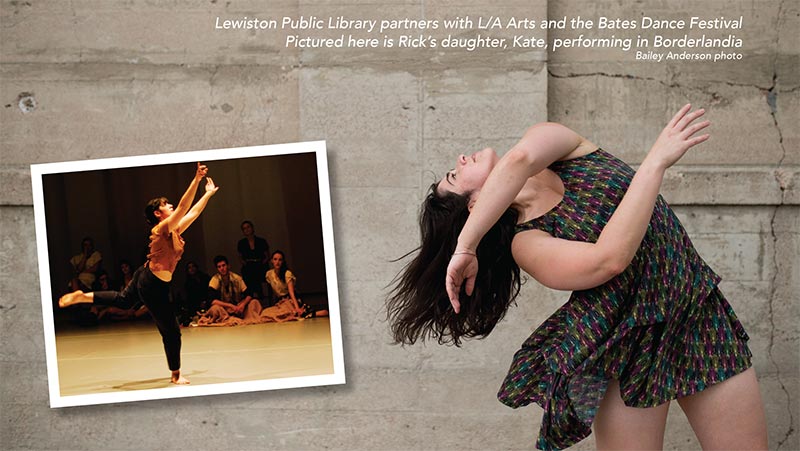

Another opportunity arose to partner with L/A Arts and the Bates Dance Festival. New York choreographer Doug Varone was commissioned to create a dance about Lewiston’s textile mill heritage. L/A Arts and LPL invited former mill workers to bring artifacts, musical instruments, and family stories to a community sharing session with Varone. “In the end, not everyone understood the final dance,” Speer smiles wryly, “but that night of sharing was amazing.”

Welcoming the newcomers

Whereas some in Lewiston saw the influx of African immigrants in the early 2000’s as a burden, Speer saw more opportunities. LPL became the perfect laboratory to foster empowerment for this influx of new Mainers over the last 15 years.

Speer made this analogy: “We were able to experience the same thrill Marsden Hartley did in the late 1800s with the Franco invasion: new languages, new colors, new culture.” An historical perspective reminds us that such shameful prejudice should never be repeated. “All of us on the staff feel good about making the library a welcoming place for everyone. To allow people to achieve their dreams of education and integration was a whole new facet.”

Ed Barrett called today’s LPL “a gathering place where we can integrate the newcomers into society.” Under Speer’s direction, LPL became a ‘safe place’ for kids and teens in the downtown neighborhood. He received a grant from the Stephen & Tabitha King Foundation to hire two workers from the Somali community, to focus on families and connect to the new-Mainer community.

In 2004, Speer received a New York Times Librarian Award, in recognition of the initial service LPL provided to the immigrant community, making it a welcoming place and offering English language-learning materials for beginners. Perhaps Speer should receive an award every year, for continuing to fulfill his personal mission to serve the community in whatever way is needed.

Art of the deal

Although expansion of the library was in the works well before Rick was offered his position in 1984, it took over a decade to be accomplished. The near-tripling of the facility’s size was full of twists, turns, and sheer luck.

Speer credits Al Gamache, a former chair of the library’s board, for starting the ball rolling, and Lucien Gosselin, then City Administrator, for having the fortitude to ask the council to get an architect to look at some possibilities back in 1988. Speer and the Board developed a facility program with conference rooms and meeting halls, so LPL could become a true community center.

But there was frustration. The initial plan hit a bump with an economic downturn in 1990 and it was clear it would not get funded.

At the same time, the Auburn Public Library began talking about its facility needs. A joint study committee was assembled, and even went through two iterations over four years. Says Speer, “We joked about building an island in the river for it.”

The next thought was to purchase the vacant Pilsbury Building that sat behind the 1903 Carnegie library building and connect them. That idea withstood a 1992 feasibility study, and won approval in 1994. Unsurprisingly, Phase 1 bids were over budget. “That’s how I learned about ‘value engineering,’” Speer notes wryly. “We came up with a plan we could afford, although it left two sections unbuilt.” The cultural center and archives would have to wait.

The Friends of the Library, a non-profit fundraising organization, were stalwart supporters of LPL. But when they were asked to raise $1 million they protested, “We just do bake sales!” Board Chair Steve Kottler identified individuals for a fundraising group to work within the Friends structure. These included attorney John Bonneau, Jan Phillips and Anne Harward (wife of Bates College President, Don Harward). Speer jokingly refers to this transfer of power the “bloodless coup,” as the original Friends willingly stepped aside.

The first phase was completed in 1997 and the second, funded by the Friends of LPL, was completed in 2000.

Phase 3 of the project may never have happened without Larry Raymond, an attorney whose client, John Callahan, was looking for places to put resources from his estate. Raymond, then Chair of the Library Board, steered him toward LPL. In 2005, the Library completed its Marsden Hartley Cultural Center, which includes a computer lab, historical archives, and Callahan Hall, a performance and meeting space named for its generous donor.

Technology revolution

Technology was already in the plan for expansion, albeit in primitive stages. “We had the Readers Guide on CD Rom,” Speer notes, “and networked CD drives to do in-house database searches.” But no one yet knew how the world wide web would change everything.

In 1990, LPL staffer Karen Jones came back from a librarians’ conference in Atlanta and said, “Rick, we have got to learn about the internet- that’s all they talked about.”

Speer started doing some research. With a few colleagues, he formed the Androscoggin Valley Community Network (AVCNet), including Rob Spellman, head of Information Services at Bates, Roger Fuller at Oak Hill High School (now a state representative), Jim Hart at the Auburn School department, and Bruce Hall from the Lewiston School department. Back then, only colleges, universities and government agencies had access to the internet. AVCNet pulled together a local computer bulletin board system that dialed in to Bates everyday for the updated feed. Spellman was willing to share news groups and email through the Bates’ system.

For its time, this service was nothing short of revolutionary. Speer boasts, “We set up our own email domain, and we had six different bulletin board systems. Before anyone heard of an ISP, we were offering email free of charge in LA. I’ll never forget that.”

During Speer’s tenure, access has grown to 64 computer stations, plus mobile devices, free wi-fi, and a crack staff which provides technical support.

New role for today’s library

Before the internet, there was the Reference Desk. Speer reminisces about his days in the research trenches. ”Our ‘bibles’ were the U.S. Government Manuals and the Directory of Associations. We were always on the phone with senators’ offices in Washington or various national organizations.”

Now, if we can just “google it,” why do we need the library?

Speer points out that it takes a true professional to show people the nuances of research. His talented librarians are adept at identifying ‘fake news,’ and navigating high-end databases for full-text journal and magazine articles. Speer boasts, “They provide lots of added value.”

One loss is another kind of gain. While LPL book circulation is dropping for print books, use of downloadable books is expanding. Your library card gets you e-books or e-audiobooks on your Kindle or iPhone.

Many families still rely on LPL’s work with partners like Promise Early Education Center (nee Headstart) and Advocates for Children to support their preschool reading needs. In addition, an LL Bean grant was used to initiate the BookReach program, supplying 40+ volunteers with books to read and leave behind at home daycares.

So here’s what’s new. In the last 5-year plan, LPL identified two areas of need: to support teens, and to help the refugee and immigrant community integrate into American life.

LPL is supporting teens academically with technology and STEM support, including work with circuits, programming, and robotics. Minecraft is very popular here. LPL is also developing a makerspace with circuitry and 3D printers, in addition to expanding teen collections of books, music and video, and graphic novels.

LPL supports English Language Learning and workforce development, by working with partners like Lewiston Adult Education and Literacy Volunteers. They also provide tech support to users in these communities by providing devices, wi-fi and plenty of handholding.

Retirement

An avid outdoorsman, canoeist, backpacker, and amateur botanist, Rick Speer already has plans for how to spend his upcoming leisure time.

“I love to get into the woods on canoe and camping trips with friends. I’ve always loved beautiful landscapes,” he declares. He’s hiked the entire AT in Maine, and in Baxter State Park, and he just joined the Maine Outdoor Adventure Club.

He credits Susan Hayward, the Stanton Bird Club’s environmental educator, for this latent passion for botany. “Susan did so much for the community,” he notes, “by revitalizing the Thorncrag Sanctuary.” When Speer took a wildflower course with this consummate naturalist through Lewiston Adult Education, he became inspired to serve as a plant conservation volunteer with the New England Wildflower Society and to join the Josselyn Botanical Society. “Being in wild Maine looking for rare plants is one of my passions.”

Besides his love of books, Rick is a devoted music fan who can often be found at Guthrie’s on a Friday night. “People look at me as this cultured person,” Speer demurs, “but I’m just a rock’n’roller in a time warp.”

The Speers also dabble in dance, the art form of choice for their daughter, Kate. Now based in Denver, Kate writes arts grants and develops conceptual modern dance. Her new piece, “Borderlandia,” which received rave reviews, was named by 5280 Magazine as one of the 4 coolest things to do in Denver this month.

Sweet sorrow

In retrospect, Speer is certain Lewiston can be proud of its library. “We’ve done a good job of serving all segments of the community, and we have a lot to offer.”

What is he most proud of, as he retires? “We’ve positioned ourselves quite well to be a true community center, where people can come together face to face, interact, learn and discuss.”

Speer’s retirement party was like a primer for Who’s Who in LA, attended by a diverse group of over 100 friends and collaborators. Large helpings of praise and proclamations were served.

True to form, Speer flipped all the hyperbolic tributes into a humble expression of his gratitude for these opportunities to serve:

“This community, its people, its art, literature, music– so much that brings us soaring in life– I got to play around with all these years. Thank YOU.”